During 1922-1923, the miners at Windber, Pennsylvania went on strike for the right to collective bargaining, better wages, fair treatment by the mine operators, and to be free of the fear and intrigue that blanketed non-union coal towns.

Joining the Strike

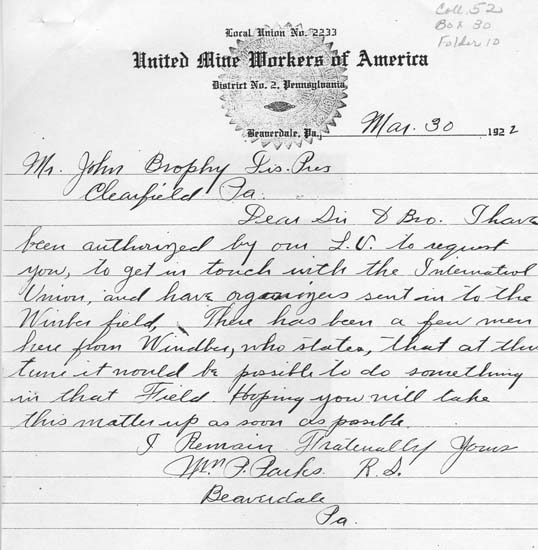

William Parks' letter to John Brophy, May 30, 1922

On the eve of the national strike, groups of Windber miners went on their own initiative to the Beaverdale United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) local (and others) to report their readiness to join the strike and their desire for union.

-United Mine Workers of America, District 2 Records. IUP Libraries Special Collections and University Archives, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

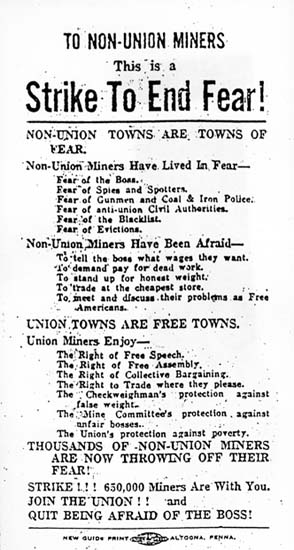

UMWA District 2 Strike Call to Non-union Miners

On April 1, 1922, organizers from UMWA District 2 invaded Windber and "Siberia"their term for Somerset County. They handed out the brochure shown below until they were arrested or chased away by the Coal and Iron Police or other company officials.

-United Mine Workers of America, District 2 Records. IUP Libraries Special Collections and University Archives, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Haulage Men Lead the Windber Miners out on Strike

Joseph Zahurak, a spragger and 1922 strike activist who later served as president of UMWA Local 6186 from 1938 to 1977, offered the below description of how the Windber strike began.

They [the miners] come out on the field in 1922. That's when they first get out there. The haulage men of Berwind-White--the haulage men, I mean mine motormen and spraggers. They was in contact with all the miners in the mine because they always ordered their cars, the amount of empty cars that they wanted or the loads that they pulled out, the haulage men. So the haulage men got together in 1922 to get it organized to come out on strike, and we avoided these people that--informers. Make sure they didn't contact them so they don't know anything about it. So in 1922, when April 1st come, a union holiday, they surprised Berwind-White, shut them down completely [emphasis]. Even the captive mines, Bethlehem Steel, US Steel, and all them. They was all shut down. And Frick Coal Company in Pittsburgh. So in 1922, it was quite a battle.

-Joseph Zahurak

-Joseph Zahurak, interviewed by Mildred Beik, October 7, 1986. Millie Beik Collection, IUP Libraries Special Collections and University Archives, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Grievances

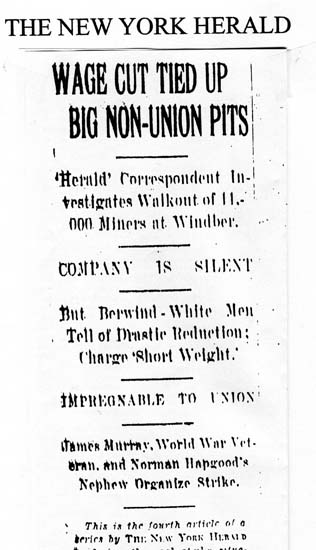

New York Herald Article on the Non-union Walkout

In April 1922, the New York Herald and other newspapers throughout the country expressed great surprise that non-union miners in Windber and elsewhere had joined the strike for union. In doing so, southern and eastern European immigrants were defying prevailing American ethnic stereotypes about their "docility."

-New York Herald Tribune, April 26, 1922[?]. Scrapbook, Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

List of Six Grievances

On May 28, 1923, UMWA District 2 President John Brophy presented a statement to the U.S. Coal Commission, which was studying the "sick" coal industry. In it, he explained the major grievances of Windber and other non-union miners that had brought and kept them out on strike for union.

Such a condition in a free country could not last forever and the miners at non-union mines were only waiting for the opportunity to assert their rights. The occasion was the great coal strike of last year. Only a short time after the strike was declared in the union fields the miners in the non-union mines joined us. The strike of the union miners was for a continuation of the wage rates; that of the non-union miners was more, it was also a strike to end fear. Nearly 25,000 miners of the non-union fields in our district answered the strike call, and a great number of them, after 14 months, are still on strike.

To be more specific they struck:

- For collective bargaining and the right to affiliate with the union.

- For a fair wage.

- For accurate weight of the coal they mine. (Experience teaches us that this can be assured only when the miners have a check weighman).

- Adequate pay for "dead work."

- A system by which grievances could be settled in a peaceful and conciliatory spirit by the mine committee representing the miners and a representative of the operator.

- By above all, they struck to assure their rights as free Americans against the state of fear, suspicion and espionage prevailing in non-union towns. Against a small group of operators controlling life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness of large numbers of miners. To put an end to the absolute and feudal control of these coal operators.

The last mentioned point being of greatest significance not only to miners, but to all American citizens. I shall take it up first. It is by reason of such absolute control that the other grievances exist in non-union fields. How does this control operate in practice? We will quote an authority not connected with.

-John Brophy, Clearfield, Pa., to Hon. John Hammond, Chairman, and Members of the United States Coal Commission, Washington, D.C., May 28, 1923. Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

A Battle on Many Fronts

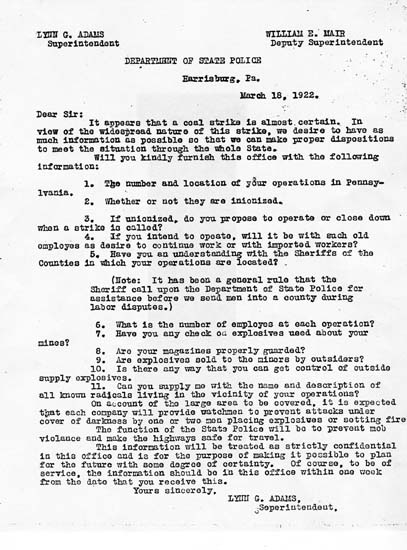

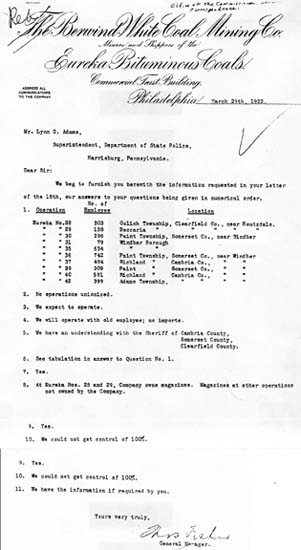

Before the strike, on March 18, 1922, Lynn G. Adams, Superintendent of the State Police, wrote a secret letter to the coal operators asking for confidential information about their operations to help the police during the strike.

The letter strongly supports the strikers' view that the State Police were not impartial upholders of the law and order, but allies of the coal corporations. Here is Berwind-White Coal Mining Company's response to Adams' letter.

Lynn Adams' State Police letter to Coal Operators, March 18, 1922

Berwind-White Coal Mining Company's Response, March 29, 1922

-Pennsylvania State Police Records, RG 30. Pennsylvania State Archives, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Arbitration and National Settlement

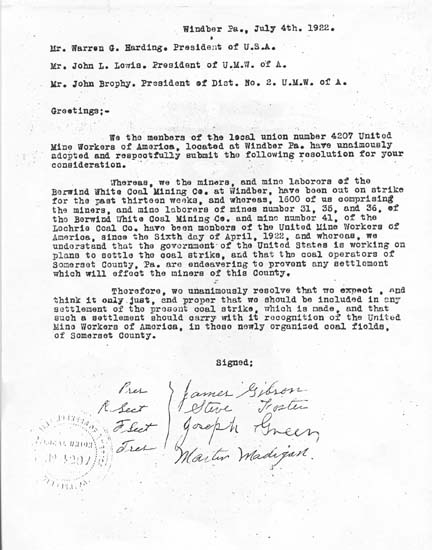

In July 1922, there was increasing talk about government arbitration and concern about some sort of national settlement of the strike.

To press for their inclusion in any final strike settlement, Windber UMWA Local 4207 and other newly founded Somerset County UMWA Locals sent letters to U.S. President Warren G. Harding, UMWA President John L. Lewis, and UMWA District 2 President John Brophy.

Windber UMWA Local 4207 Letter Requesting Inclusion in any Strike Settlement, July 4, 1922

-United Mine Workers of America, District 2 Records. IUP Libraries Special Collections and University Archives, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Continuing After Exclusion from the National Settlement

For publicity and relief-raising efforts, this photography of several thousand Windber miners, dressed for the occasion, was taken in an open field soon after their decision to continue the strike for union.

-United Mine Workers' Journal, October 1, 1922.

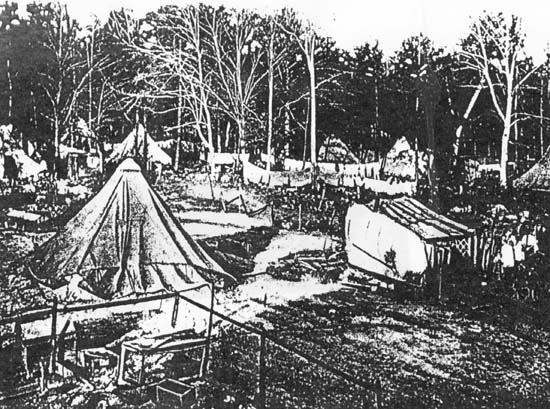

UMWA District 2, friends, and relatives were unable to help relocate all those mining families who were evicted in Windber. By September 1922, tent colonies like this one dotted the Windber landscape.

-David Hirshfield, Statement of Facts and Summary of the Committee Appointed by Honorable John F. Hylan of New York to Investigate the Labor Conditions at the Berwind-White Company's Coal Mines in Somerset an Other Counties, Pennsylvania: (New York, December 1922), p. 10.

Pearl Leonardis on helping evicted families:

When they went on strike, Berwind threw [out] everything. They [Berwind people] went there and throw everything out from these families. That was a shame. You don't do stuff like that, you know. You stop the book [storebook]. You don't give them nothing. You don't give them the power, okay, the light, but don't throw their stuff out. Everything was throwed out, and those people were stranded. They were out there picking up their things.

So we had to, I told me husband, "Well," I said, "you go pick some families up."

So they went out, too, and they bring back a family...

This lady had two children, and she had a brother-in-law, herself, and her husband. So I said, "Okay, I'll give you room." I took the dining room, all the parlor. I pushed everything, brought every piece of furniture from upstairs, and I made her a bedroom out of my parlor. We brought her furniture, everything we could find upstairs and brought it for her.

I said, "I have a bunk bed. I'll put him [the brother-in-law] with our men upstairs. No don't you say no. He's a brother. We are all on strike and he's on strike, and we have to take care of these men." And we had a family. Then this other one [the neighbor] did like I did, and we put up another family.

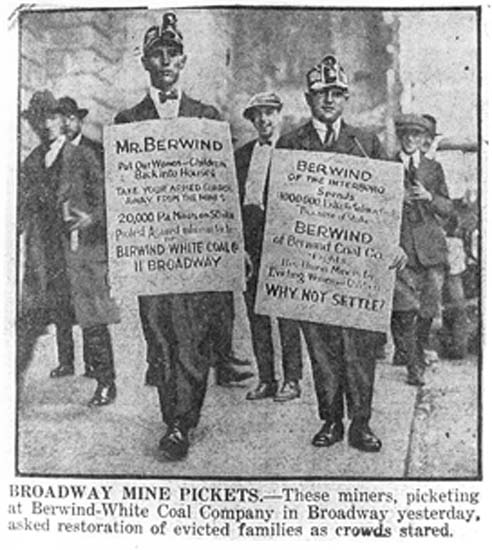

New York City Campaign and Inquiry

In the wake of their exclusion from the settlement, Windber Miners picketed on Broadway in New York City to bring further national attention to their plight.

-Unidentified newspaper photo. Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

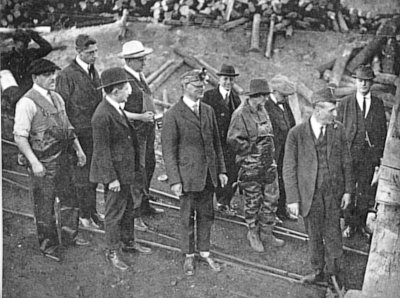

-Photograph of the Hirshfield Committee entering one of the Windber mines

Because of the Windber miners' campaign, E.J. Berwind's refusal to negotiate, and his scandalous confict-of-interest role on the Inerborough Rapid Transit System's board, Mayor John Hylan of New York City sent a committee of prominent city officials to investigate the living and working conditions of the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company's miners. This photograph shows that committee, entering a mine in Windber on November 1, 1922.

-David Hirshfield, Statement of Facts and Summary of the Committee Appointed by Honorable John F. Hylan of New York to Investigate the Labor Conditions at the Berwind-White Company's Coal Mines in Somerset an Other Counties, Pennsylvania: (New York, December 1922), p.22.

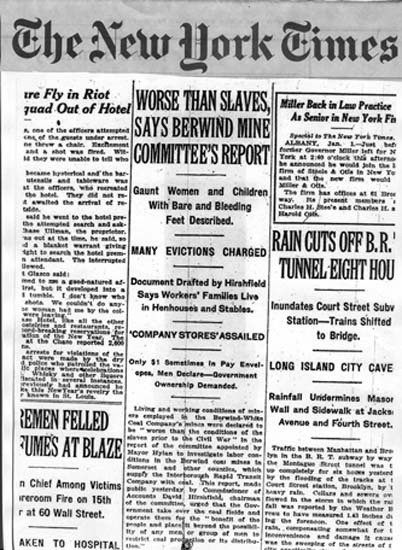

"Worse Than Slaves" article from the New York Times

The shocking conclusion of the New York City committee's report, that the "living and working conditions of the miners employed in the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company's mines were worse than the conditions of the slaves prior to the Civil War." This appeared on page 1 of the New York Times and other newspapers throughout the nation on January 2, 1923.

-New York Times, January 2, 1923, p. 1

"A Lost Strike is Never Lost"

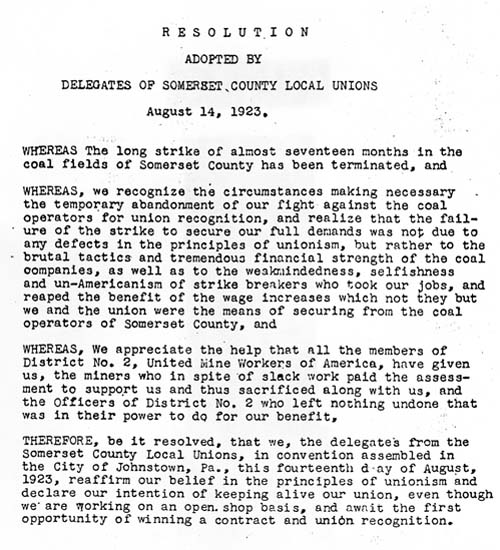

Windber and Somerset UMWA local unions reaffirmed their ongoing desire for union in this resolution, even as they found it necessary to call off their 16 month long strike for union.

Resolution adopted by Delegates of Somerset County Local Unions

-Powers Hapgood Papers, Lilly Library, Manuscripts Department, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Joseph Zahurak speaks about the coming of the union in 1933:

So then later on, after we come into it here, where we finally, after all these strikes from 1927 to 1933, when finally, the dark clouds disappeared. We got our president in there, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. And they got the law [The National Industrial Relations Act] passed where you could organize. You're allowed to organize if you want to organize. And I'm telling you, that law was passed, and the union came in. The United Mine Workers of America was short on funds and money. So they borrowed $500,000 from the American Federation of Labor to put men out in the field for expenses to go out and talk to these miners. And they brought cards for us to sign the miners up, who all wanted the union. And I'm telling you, the cards went fast! Everybody was signing up. That's 1933, when they knew that they were finally safe. It could be done. We finally had our first union meeting in Slovak Brick Hall. And after a couple of meetings in there in July 1933, we received our charter. And Berwind-White Coal Mining Company recognized the union.