Touchstones of the Past Live On in a Digital World

By Elaine Jacobs Smith

Even when he jokingly calls himself the henchman who brought an end to the IUP yearbook, Joe Lawley ’90 sounds apologetic.

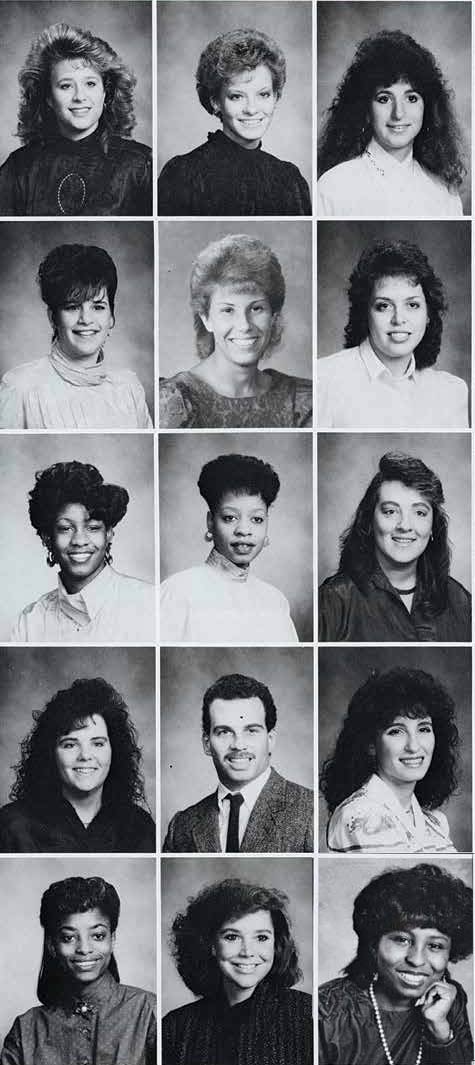

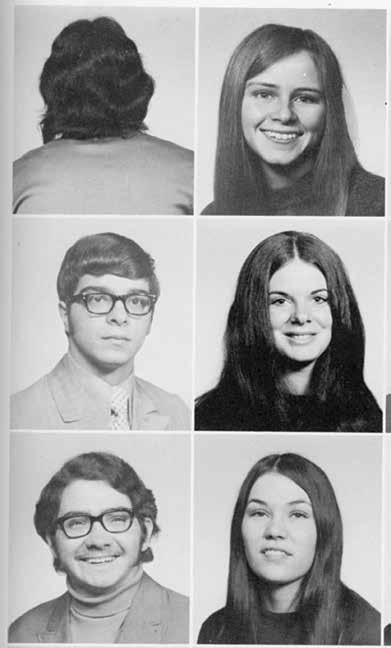

College of Human Ecology and Health Sciences senior portraits, 1988 Oak

From a practical standpoint, he had little choice. Soon after he started in 1995 as the Student Cooperative Association’s publications director, he learned that finding students to work on the yearbook was like pulling teeth. What’s more, only a fraction of seniors were sitting for their portraits—the yearbook’s bread and butter—and even fewer were buying the book itself.

“The bottom dropped out,” Lawley said. He talked with his bosses, and they agreed that after 85 straight years of publication, the IUP yearbook had run its course.

“Whether 10,000 people or 300 people wanted a yearbook, you still had to put in the work,” said Chuck Potthast M’77, who was the Co-op’s director of Business Services and Lawley’s direct supervisor. “It wasn’t cost-effective.”

The last yearbook came out in 1996—more than a century after the first. Indiana State Normal School students produced one issue of The Clionian in 1888 and one issue of The Empanda in 1897 before hitting their stride with The Instano (short for Indiana State Normal) from 1912 to 1927. The following year, uninterrupted publication continued with The Oak yearbook while the school evolved from Indiana State Teachers College to Indiana State College to IUP.

Across Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education, other yearbooks have had similar fates. Only three of the original sister schools—Bloomsburg, Mansfield, and Shippensburg—are still publishing yearbooks, although Mansfield has had production gaps, one lasting 25 years. All the other schools ceased publishing yearbooks a decade or longer ago, which seems to follow a national trend.

In an NPR story from 2010, a representative from yearbook publisher Jostens said about a thousand colleges at that time—down from 2,400 in 1995—were still printing yearbooks.

Like that story’s writer, Lawley suggests the internet is to blame—that its options for photo sharing and social networking made yearbooks irrelevant, though The Oak disappeared before the rise of sites like MySpace and Facebook.

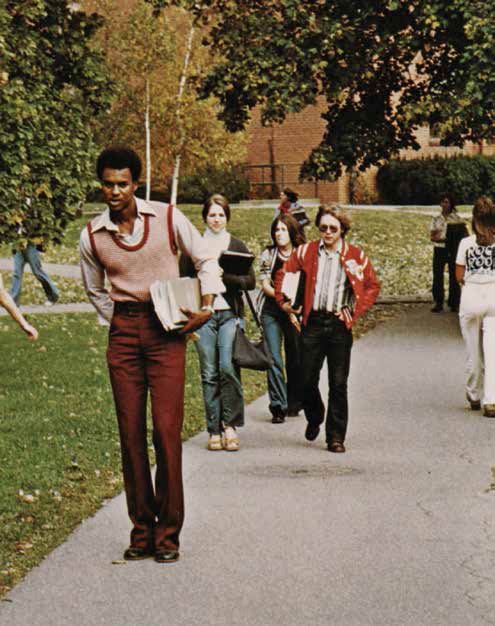

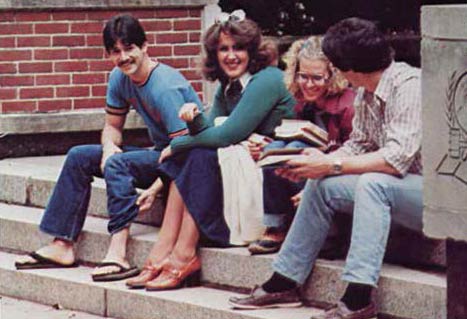

From the 1975 (above) and 1980 (below) Oak yearbooks

He also said a school’s size matters. Yearbooks remain popular at high schools, which tend to have graduating classes of a few hundred students, most of whom know one another. In comparison, a 1990s IUP graduating class was “like a giant ocean of 3,000 people,” Lawley said, and students were less likely to open a yearbook and find people they knew.

As interest in yearbooks declined, so did the incentive to work on them. The staff would begin work in September and send materials to the printer in March or April so that the books would be ready before students left in May. At that time, photos had to be developed, and page layouts were done by paste-up, not on a computer, said Lawley, who retired from the Co-op in 2019. “It was a big job.”

He thinks the long production schedule was another deterrent. “There’s no immediacy with a yearbook,” he said. In contrast, the other publication he worked with, The Penn student newspaper, had students willing to work more than full-time hours to put out three issues a week.

“Those kids—it’s in their blood,” Lawley said. “They don’t do it because it’s fun. It’s what they need to do.”

What concerns Lawley about losing the yearbook is that students may have more photos now than ever before, but they likely don’t have a record of what happened in the last year. “The yearbook,” he said, “was a different animal.”

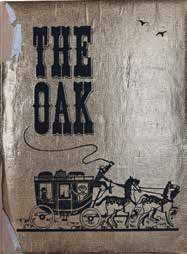

Yearbook covers from 1949, left, to 1952 were among the most elaborate.

IUP archivist Harrison Wick is well-versed in the value of primary sources, like yearbooks, commencement programs, and academic catalogs.

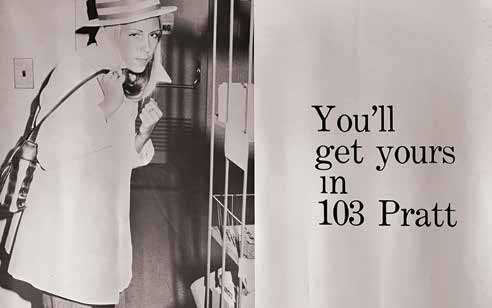

Oak editor Joanne Fedorka in a 1970s poster promoting yearbook sales

Since joining the library faculty in 2007, he has worked to make those resources—housed in the Special Collections and University Archives on Stapleton Library’s third floor—available digitally so more people can access them. That includes all 87 yearbooks, which the nonprofit Internet Archive digitized in 2009 at no cost to the university as part of its mission “to provide universal access to all knowledge.”

Alumni and current students are the most frequent yearbook users, Wick said. Alumni may ask for a high-quality scan of a particular image, or they may need several, as Mary Kreider Megna ’84 did when curating images for the 2022 IUP Marching Band documentary, Sustaining Grace. Current students often peruse yearbooks to see what students were like in the past.

“It’s fun,” he said, “because yearbooks provide a glimpse into different periods.” Their coverage of almost the entire 20th century will make them key to the IUP@150 exhibition (celebrating the school’s 150th anniversary) at the University Museum next fall.

“For some events, they are the only photographs we have,” Wick said.

Senior portraits from 1972

In early yearbooks, photos were understandably limited, but they quickly became prevalent, even in the 1920s. Wick noted that the photography was very formal, and the books adhered to a traditional structure with sections for administrators, faculty members, students, organizations, and advertisements.

With paper shortages and fewer people on campus during World War II, the books grew thin in the 1940s but were quick to bounce back before the decade’s end. The photos, and the yearbooks themselves, became more casual in the 1960s and ’70s. By the 1980s and ’90s, they were what Wick called “informal social publications”; the 1996 yearbook devotes 16 pages to world, national, and entertainment news.

Wick considers the yearbook’s heyday to be the late 1940s through the mid-1970s.

Some of the books had elaborate themes. The 1949 Oak’s inspiration was the California gold rush of a century before. It compared the gold prospectors of 1849 to the knowledge seekers of modern-day Indiana State Teachers College. The cover featured a gold-foil overlay. “It’s a very fragile book,” Wick said.

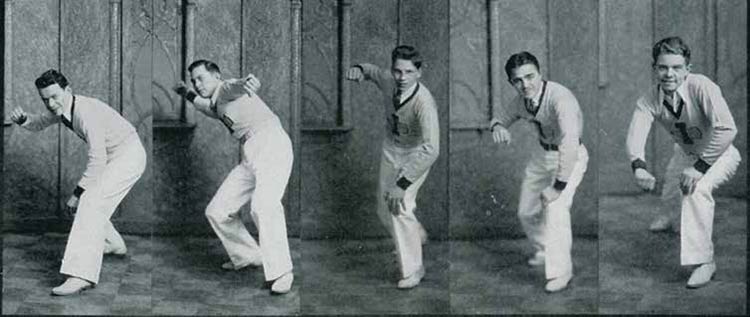

Cheerleaders from 1935

The 1950 yearbook, adorned with blue and white flourishes, celebrates the school’s 75th anniversary, or Diamond Jubilee, while the 1975 yearbook marks the school’s centennial with a foldout poster, a brief history, and a host of old photographs on top of coverage of what was the current academic year.

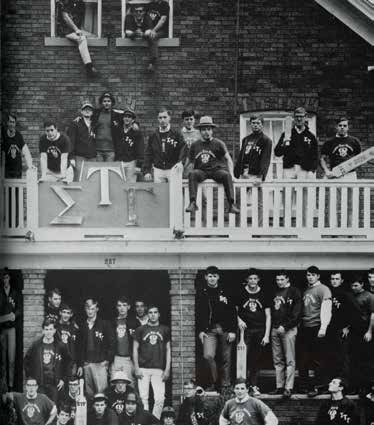

Sigma Tau Gamma brothers (1968 Oak)

Former yearbook staffer Joanne Fedorka Duffey ’77 remembers bringing photos home with her to Sayre, near the New York state border, one summer to work on the layout. She filled in as editor-in-chief in the spring of 1975 and continued in the role the following school year.

The yearbook staff was small but dedicated, she said, and worked hard to sell the book in addition to producing it.

A retired speech pathologist now living in Delaware with her husband, Dan Duffey ’74, she recently dug up a whimsical poster from the ’70s that shows her brandishing a fist and looking menacing next to the words, “You’ll get yours in 103 Pratt,” which was the yearbook office.

“People recognized me from the poster,” she said, though she’s not sure how much it helped yearbook sales.

Challenges to IUP’s ability to support a yearbook had, no doubt, been building for some time. When the end of The Oak was announced, Lawley braced for an onslaught of questions and complaints. To his surprise, he received only a single call.

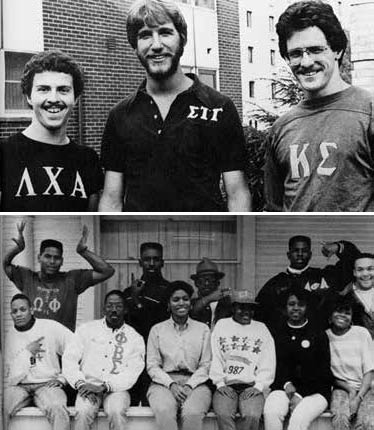

Interfraternity Council officers (top, 1979 Oak), and the Black Greek Council (bottom, 1989 Oak)

A tradition had drifted away, he said, and “nobody came to its funeral.”

Wick shares Lawley’s concerns about the historical record that died with the yearbook, especially since people tend to call on him when they want to revisit IUP’s past.

“We rely heavily on images and other publications,” Wick said, “but it’s difficult. The yearbook was a very consistent lens into its period.”

Fifty years after the 1975 Oak came out, the message on its centennial poster reads almost like a forewarning: “As stands the oak tree, sturdy and unbending against the forces of time and oblivion, so may this OAK stand, guarding against forgetfulness the memories both of work and play of your years at Indiana.”

1968 Oak

Visit the Archives

To access yearbooks and other IUP publications in digital format, go to the IUP Archives.

Hard copies of yearbooks are also available for browsing by appointment in the IUP Special Collections and University Archives on Stapleton Library’s third floor.

If you can identify people in the photos or if you have a memory to share, IUP archivist Harrison Wick would love to hear from you. He also accepts donations of yearbooks, particularly the 1987 Oak, and other IUP memorabilia.

Contact him by email at hwick@iup.edu.

Yearbooks in Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education

Institutions and the last year they published a yearbook

Bloomsburg* — Still publishing

California† — 2015

Cheyney — 1988

Clarion† — 2000‡

East Stroudsburg — 2010

Edinboro† — 2002

IUP — 1996

Kutztown — 2008

Lock Haven* — 2009**

Mansfield* — Still publishing**

Millersville — 2012

Shippensburg — Still publishing

Slippery Rock — 2007

West Chester — 2014

*Integrated into Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania in 2022

†Integrated into Pennsylvania Western University in 2022

‡Clarion’s Venango Campus had its own yearbook, last published in 2003.

**Includes a gap of 25 years or more

IUP archivist Harrison Wick assisted in collecting this data.