At the side of a road in rural Mercer County, a historical marker installed in 2019 briefly tells the story of Pandenarium.

It was a hundred-acre site just north of Indian Run, where 63 free African Americans settled in 1854, more than six years before the start of the Civil War. Many were released by Virginia physician and plantation owner Charles Everett upon his death, and they brought along others whose freedom they had purchased. Upon their arrival at the site, they found houses, gardens, orchards, and more that Everett, through his nephew, had paid nearby abolitionists to build.

Had the historical marker come a decade earlier, the story may have ended there. But thanks to the efforts of two former students in IUP’s MA in Applied Archaeology program, the story continues—on the marker and in real time—with details about the lives of the community’s settlers.

As the only researchers to have excavated this historic site, program graduates Angela Jaillet-Wentling M’11 and Samantha Taylor M’18 followed a similar path to Pandenarium. While at IUP, both had expressed interest in the African diaspora, and faculty member Ben Ford , now chair of the Anthropology Department, suggested the settlement as a research focus for their master’s theses.

Ford had learned about Pandenarium through Mercer County archaeologist Bill Black.

“The site represents an important and little-known aspect of Pennsylvania history,” Ford said. “There was a lot of partial information, and archaeology excels at filling in the cracks of written history.”

“Archaeology excels at filling in the cracks of written history.”

Originally from Sandy Lake, just 10 miles north of the site, Jaillet-Wentling was unfamiliar with Pandenarium before pursuing her research. But chances are its early residents hadn’t heard of it either. The name—an apparent reference to “Paddan-aram,” the Hebrew term for an upper Mesopotamian kingdom in the book of Genesis—began appearing in text only in the 20th century, she said.

Jaillet-Wentling described her initial research as a landscape-level analysis to identify such things as the site’s location, boundaries, and building remains. She’s a member of the inaugural class of the MA program, which in 2021 ranked third in the world in producing registered professional archaeologists.

As she read about Pandenarium, Jaillet-Wentling found that the narrative focused on Everett, the White abolitionists, and their “great and wonderful deeds.” In what little was mentioned about the settlers, she detected bias and set out to find the truth.

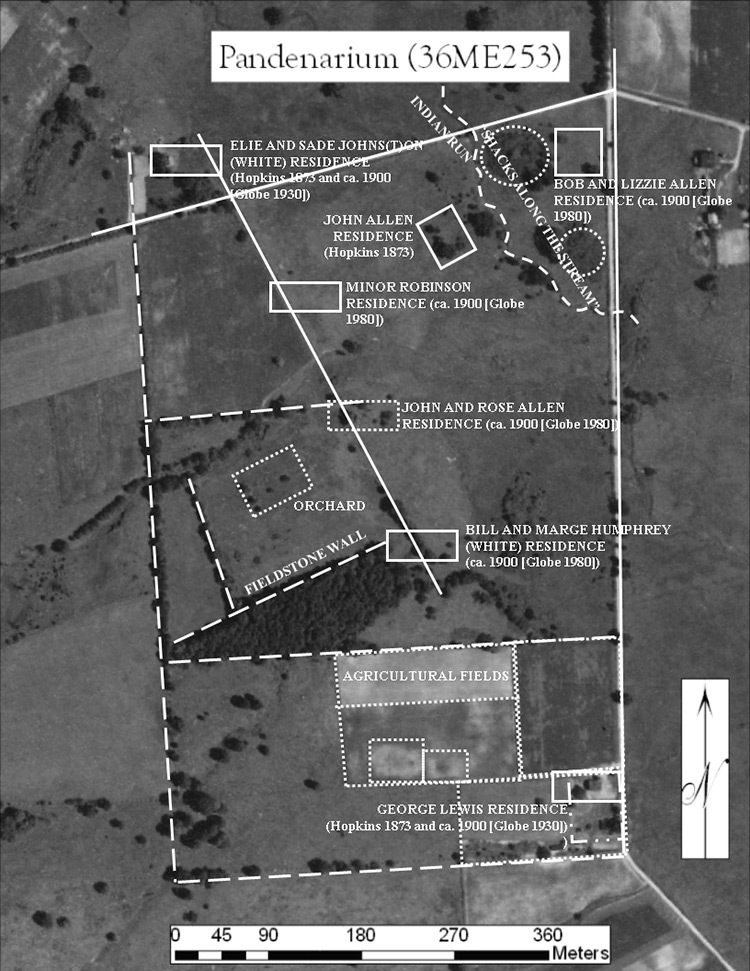

“There was a phrase that kept coming up in the historical texts,” she said. “They came in, there were 24 houses that were built for them, but they chose to build ‘shacks’ along the stream. The story went that, the first year, they were flooded out, and the settlement was a failure, which is very different from what we found.”

Angela Jaillet-Wentling indicated the boundaries of Pandenarium and its residences and other features in white on this 1939 aerial photograph.

Through her analysis of old maps and aerial photos, her review of records, and her archaeological research—all of which she has continued on her own time since her IUP graduation—Jaillet-Wentling found that the community existed through the 1930s.

“So, it’s a pretty long-lived settlement,” she said.

Her research focused on original residents John and Rosie Allen, whose son Bob also raised his family in Pandenarium, but far in the northeast corner, suggesting an attempt to integrate into the larger community, Jaillet-Wentling said.

“They started to push boundaries, and they did it in different ways,” she said. “They built toward areas where they could expand into the community. They also intermarried, racially. And they started working outside of the agricultural community.”

These findings, she said, offer insight into “how these people negotiated a landscape that was new to them but also a freedom that was new to them.”

Benefiting from the groundwork Jaillet-Wentling had laid a few years earlier, Samantha Taylor set out to do something more specific—a comparison of ceramics from Pandenarium with ceramics from three other sites: a European American village in Beaver County; an enslaved community within Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, which was very close to the Pandenarium settlers’ former plantation; and Timbuctoo, a settlement in New Jersey that was also home to free African Americans.

Excavating around the half-cellar foundation of John and Rosie Allen’s residence, Taylor enlisted the help of her thesis committee, fellow students, and community members—including during a public archaeology weekend in 2017—to collect enough artifacts for the comparison.

She found that, overall, Pandenarium’s ceramics were most similar to Timbuctoo’s, likely because of their similar socioeconomic status. However, in diversity of ceramics, which points to the use of hand-me-downs, Pandenarium had the most in common with the enslaved community of Monticello.

“So, despite maintaining this new socioeconomic status,” Taylor said, “they still had characteristics and behaviors that were representative of their previous lifestyle.”

Her goal, she said, was to fit Pandenarium into the story of the African diaspora in the Mid-Atlantic and Pennsylvania.

“I can’t remember how many artifacts we recovered,” Taylor said, “but it was thousands and thousands. So, now there’s this body of information that somebody else can use, like I did with the other sites, which further solidifies Pandenarium’s spot in comparative archaeological and African diaspora research.”

Jaillet-Wentling, who recruited Taylor to coauthor an article on Pandenarium for the April 2021 edition of Historical Archaeology , is pleased they’ve been able to “add depth and nuance to a narrative that wasn’t there previously.”

“We know histories are biased, but to see it confronted with archaeology is a very dramatic thing,” she said. “The voices of the African American people who lived there were essentially written out of the history. But that’s the real strength of archaeology—that words and people can lie, but it’s much harder to do that with your garbage.”

“We know histories are biased, but to see it confronted with archaeology is a very dramatic thing.”

Both alumnae said the most exciting and rewarding part of their research has been connecting recently with descendants of Pandenarium residents, found with the help of historian Frank Bell.

As archaeologists, they said it’s important that the descendants drive the narrative. Otherwise, they as researchers are interpreting a history and culture that belong to someone else.

“Now that we’ve identified descendants and begun the conversation around their histories, we have the chance to tell their story together,” Jaillet-Wentling said.

Ford hopes that IUP students, too, can be part of that effort through a future field school.

“I’d like IUP to remain active at the site,” he said, “as long as the community will have us.”